Part 1 of 2 parts: Maria Clara the Brave

When Jose Rizal’s fictional governor-general in the Noli Me Tangere remarked that Maria Clara was the most virtuous of daughters, he wasn’t referring to her Catholic moral virtues, but rather, to her courage. Yes, Maria Clara was actually brave.

Her courage, however, is hardly talked about when MC is discussed. Instead, what surfaces is this popular sentiment: Filipina women aren’t like her or don’t want to be like her.

Generations Apart

Indeed, MC is different from today’s Filipina. Just by her outfit alone, she is different. We wear the Maria Clara only on special occasions whereas MC had to drag her saya everyday across the floor, brick, or mud. She had company though, American women would raise their hemlines to expose their ankles only in the first decade of the 1900s.

Over a hundred years of the feminist movement, American colonization, WW II, and two female presidents separate the current-day Filipina from MC. In the Philippines today, there are more females than males in high school and college, women are in the police force, and women can read books that MC’s friar confessor would have burned.

False Advertising

But is MC really everything we Filipinas don’t want to be?

She’s been advertised as weak or prone to faint, demure, and a mere oriental decoration. Rizal never called her any of these, though. Sure, she got sick, was raised in convent school, and was described as beautiful in so many poetic verses. But she was brave too.

“Rizal nowhere announced that he was going to depict an ‘ideal woman’ or an ‘ideal Filipino woman’ — whatever that may be. Being a true novelist, he set out to create just one particular person, a single definite individual — and he succeeded so well that his heroine has become a folk-figure, the only one of all his characters who has attained this highest form of literary immortality.”

Nick Joaquin, The Novels of Rizal, An Appreciation, December 1951

According to historian Nick Joaquin, during the Philippine mock-Victorian era in the early 1900s, MC was heralded as the ideal Filipina woman. From a vibrant girl, she was transfigured into a refined señorita.

She became the muse of such an era without Rizal’s consent nor his definition of what an ideal woman is. In the novel and in his lifetime, Rizal never mentioned MC was the ideal Filipina.

In the 1930s, feminists criticized MC the ideal Filipina. They said MC was a caricature of what women were like in her time — that Rizal was making fun of her. Rizal did poke fun at his characters and their cultural practices. But when he did, he was funny. That doesn’t happen with MC.

Both feminists and Victorians got MC’s identity wrong. So who is the real MC? Let’s begin with her beginnings.

Her Parentage

Trigger warning. We are entering 19th century Philippines, when the only ones who were called Filipino were the Creoles or Spanish descendants born in the Philippines. Above the Creoles, were the Peninsulares, born in Spain, Iberian Peninsula, and who arrived in the Philippines as government official, soldier, or priest. Below the Creoles were the Indio, Chino, Moro, and everyone else.

MC’s father Tiago was a de los Santos. This is a non-Spanish surname, which means he was either an Indio or a Chinese mestizo. At a party in the de los Santos home, in a conversation among guests, Padre Damaso calls the Indio indolent. Another guest nervously whispers that their host is an Indio. Damaso brushes off the reminder and says Tiago doesn’t think he is an Indio. After all, according to the narrator, Tiago gained social position by marrying Pia Alba.

Alba is a Spanish name. The union of Tiago and Pia made MC, a Creole mestiza. MC’s boyfriend Juan Crisostomo Ibarra was a fourth generation immigrant with mixed ancestry, thus he was a Creole mestizo. Damaso, who is MC’s godfather and biological father, was a Peninsulares.

I mention the social classes of the main characters because they unlock Rizal’s Noli. The 19th century class structure provides context to why Damaso wants to keep MC and Ibarra apart.

MC’s Fiancé: better a penniless Peninsulares than a wealthy Creole

After the ex-communication of Ibarra, Damaso wanted MC to marry Alfonso Linares. Linares was a poor new arrival pretending to have been private secretary of the ministers of Spain. Since 1869, many Spaniards like Linares arrived in the Philippines sailing through the newly opened Suez Canal. It was a faster route for these men who came with the mission to marry a Filipina heiress.

To Damaso, MC was better off with a poor Peninsulares than a rich Creole. His reason: Ibarra would make her unhappy. “How could I permit you to marry a native of the country, to see you an unhappy wife and a wretched mother? As a mother you would have mourned the fate of your sons: if you had educated them, you would have prepared for them a sad future, for they would have become enemies of religion and you would have seen them garroted or exiled; if you had kept them ignorant, you would have seen them tyrannized and degraded.”

We need to see this situation through Damaso’s eyes: the Peninsulares had close ties to Spain. He had friends there and he knew his relatives there. The Creole only knew his cousins through stories from his parents. The Peninsulares thus identified with the mother country and church better than a Creole like Ibarra.

Creoles were loyal to their country of birth

In the American colonies of Spain, the first clamors for independence erupted from the Creole class. This, too, happened in the Philippines. Ibarra fit the role of filibustero even if he was innocent of revolt. He had gone to school in Europe and had brought home the idea of educating Indios, (heaven and Peninsulares forbid!). His family had even restyled their name from the original Eibarramendía to Ibarra.

When Ibarra was sent to jail, people at the sidelines commented: “But it’s said that this filibustero is the descendant of Spaniards.” “Oh, yes! It’s always the creoles! No Indio knows anything about revolution!”

The Non-fiction Creole who inspired Rizal

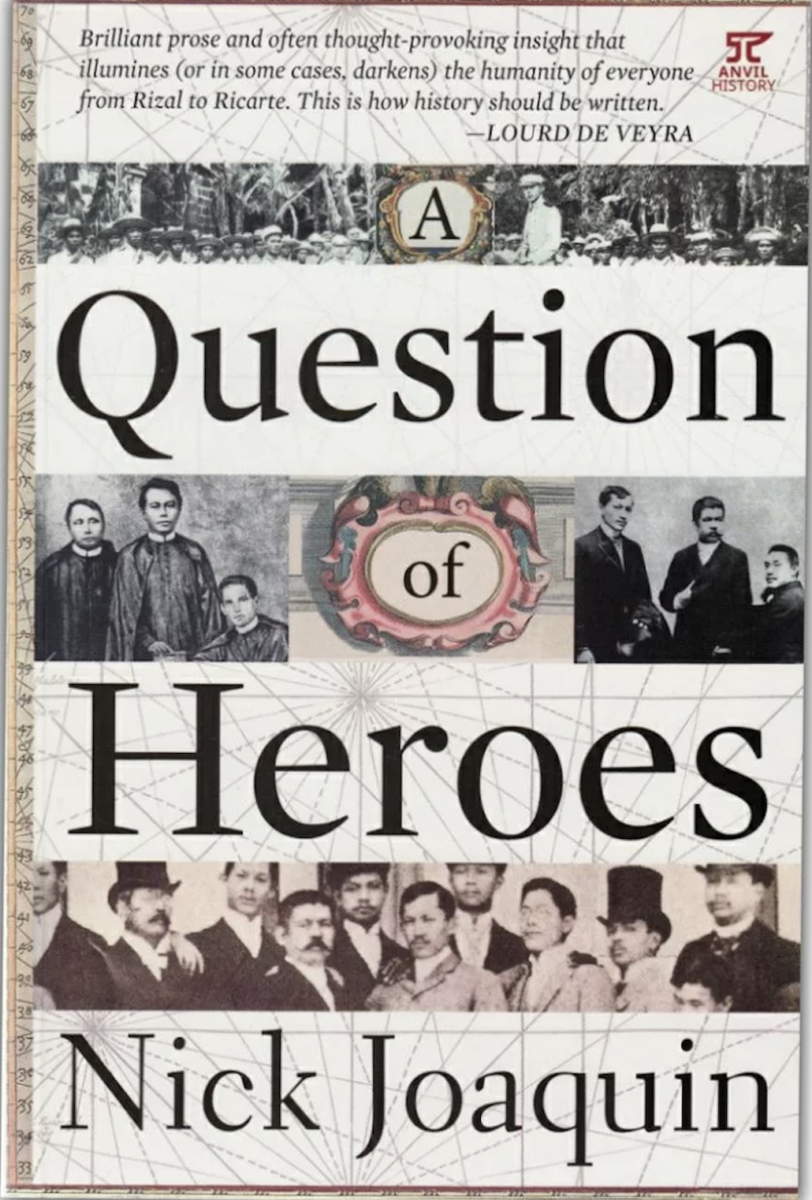

Nick Joaquin, in A Question of Heroes, shows that the fictional Creole Ibarra was similar to the non-fictional Creole Padre Jose Burgos.

In 1872, Burgos was garroted for being part of the Cavite Mutiny. Like the fictional Ibarra, he had ideas for reform and had denied being a part of the revolt. Burgos was also well educated like Ibarra. He had a doctorate degree in theology and canon law. Rizal dedicated his second novel, El Filibusterismo, to Burgos and his co-martyrs.

Now back to MC.

Convent School and Music

MC began her day with a mass and ended it with a prayer. She confessed regularly. Everyone did, except for a few like Ibarra’s father who did not confess at all. This failing bolstered the charge of heresy by Damaso against Ibarra’s father.

Rich girls like MC went to convent school. There, MC learned how to sing and play the piano well. Her father liked to show off her skills to his guests and she played even if she wasn’t in the mood. When she just wanted to mourn the ex-communication of Ibarra, she still presented herself at the party of Tiago.

Chaperones and going against the norm

MC’s mom died giving birth. Aunt Isabel, a sister of Tiago, took care of MC. As was practiced at that time, Aunt Isabel ensured that in the social functions attended by the grown-up MC, the women were separated from the men. She also chaperoned MC whenever she went out or when she had male visitors.

On Ibarra’s first visit after his arrival from Europe, after pleasantries, MC rebelled from the norm. She moved to the azotea where she could be alone with her boyfriend. Aunt Isabel conceded: “that’s better, there you’ll be watched by the whole neighborhood.” No kissing happened on the azotea — not yet anyway.

The Farewell

The next time they see each other on the azotea, it is nighttime, the city is asleep. They both know this may be their last meeting. She is to marry Linares and he is a fugitive. Before Ibarra leaves, she kisses him on the lips again and again. She embraces him and then pushes him away to leave.

This clandestine kiss and embrace is a revelation. It bares an MC different from the ideal Filipina praised by Catholic conservatives and mocked by feminists. Indeed, 19th century norms and that heavy dress did restrict MC, but she defies being placed in a box labeled the ideal stereotype.

Maria Clara was passionate and very much her own woman.

—- ⬤ —-

Side notes….

Leave a Reply