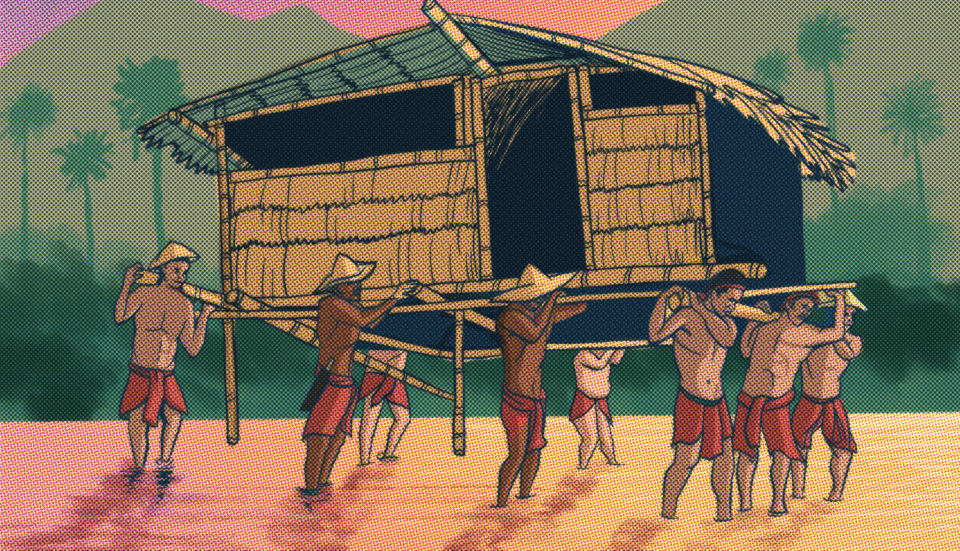

In Bohol, members of an organization called Dayong help the bereaved carry out rites for their dead. Dayong is a verb referring to two or more persons helping each other carry a load or a burden. Dayong also means getting together to communally accomplish a task. In this sense of community cooperation, it is like the Tagalog word bayanihan. From the experience of bereaved families in Bohol, we can say that dayong is how Visayans do bayanihan. Dayong is pronounced da-yong by most Visayan speakers and dad-jong by Boholanos.

It takes a Village to bury the Dead

Six male members of the group Dayong carried the coffin of Eda’s father in the funeral rites last March. This was their way of honoring the dead and of also fulfilling their obligation to the Dayong.

The Dayong is composed of some 100 neighboring families in the municipality of Catigbian, Bohol. The organization or Kapunungan is aptly named Dayong because the members help one another carry the weight of their duties to the deceased.

The Assistance of the Dayong

Each member family contributes P200 in cash, rice worth P100, and a bundle of firewood to the bereaved family. A representative of each family also serves the bereaved in his best capacity. For example, those who know masonry and carpentry are assigned to construct and seal the niche at the cemetery. Others take charge of cooking, serving, or washing the dishes for the feast served on the day of the burial.

In the past, the Dayong used to build the coffin. Today, the monetary collections are used by the bereaved to buy a coffin and pay for the funeral services.

“One of the institutions of Filipino society is to show a spontaneous and sincere effort to ease the burden of grief of the afflicted... “

Aparece 1960: 165.(Encyclopedia of Philippine Folk Beliefs and Customs, Volume 1 by Fr. Francisco Demetrio, S.J.)

Dayong in the Philippine Islands

Across the Philippines, especially in the less urbanized areas, many Filipinos organize themselves into their own version of the Dayong.

The organizations come in different names but with the same purpose. Manigsuon means to help each other like siblings. Bubu-ay means to pour water or in this case, pour donations. Damayan means to sympathize and help someone in need.

These groups do as little as collect an agreed amount like P50 per member and turn it over to the family of the deceased. Or they do as much as the Catigbian Dayong which even has communally owned cookware and dining utensils for use in the funeral feast.

The Rites

Since the members of the Catigbian Dayong are Catholic, they have a nine-day novena schedule for the dead. After the funeral and the ninth day prayers, a feast is held by the mourners.

The pre-Catholic Visayan had funeral feasting after the burial and again on the ninth day after the burial. The urge to carry out these feasts remains strong today even in the face of economic difficulty. If the funeral and the ninth day are held on separate days, the family is expected to host two meals. To economize, most families schedule the funeral on the ninth day.

In urban centers, a snack at the cemetery is usually served after the burial. On the ninth day, a feast is also the norm.

According to Eda, the Dayong had been a great help in carrying out the rites that her father had expected.

How the pre-Catholic Filipino did it:

Rite, Ritual, and Ceremony: Ethnohistory and Archeology of Death in Late Precolonial Cebu by Jose Eleazar Bersales

“Nine days after the burial and not earlier, a paganitu called pagpasaka would be performed by a babaylan. (The determination of the days may be an influence by Christianity since Alcina’s informants included Christian converts.)”

Roots of the 40th Day Catholic Rite

On the 40th day after death, the Filipino Catholic family gathers again for prayers and hosts another meal. The Catigbian Dayong no longer participates in the preparation of this meal which is hosted by the family alone. There are often less attendees to this occasion compared to the burial feast, as was the case with Eda’s family.

According to Rev. Fr. Genaro O. Diwa, the 40th day rite has cultural roots. The pre-Catholic Filipino had a long mourning period punctuated by many sacrifices to the spirits called paganito. The early friars gave these cultural practices a Biblical meaning. The inspiration is the 40-day period after the resurrection of Christ which culminates in his ascension.

With the passage of time, the paganito customs of the ancient Filipino evolved into Christianized rites.

Beliefs and Practices

Aside from ensuring that burial rites are carried out, Dayong members also teach the younger generation about their beliefs concerning the wake or haya.

During the haya, the bereaved family is disallowed from sweeping inside the house or combing their hair inside the house. Items given at the wake or the cemetery, be it food or candles, should be consumed or left in the area. These practices are believed to help the family ward off bad luck or keep them from suffering another death immediately.

The younger generation may no longer find these practices important. One belief, though, has remained intense through the centuries: the dead should not be left alone during the haya. This is why in the evening, mourners play mahjong to keep each other awake and be with the dead in the last days before burial.

Other Pre-Catholic Practices Still Done Today

Ancient Visayans wore white during the mourning period just like they do in Catigbian today. They also placed personal objects such as ceramic bowls inside the coffin. Today’s mourners place less chunky objects like clothing or a favorite religious item of the deceased like a rosary or prayerbook.

While eulogies are now delivered in churches, the pre-Catholic way of extolling the dead called canugon still exists. But today, it is no longer delivered by a hired mourner but by someone close to the deceased. Canugon or kaanugon means what a waste! A mourner would arrive and speak aloud. He would announce the good deeds or exploits of the dead. I’ve personally witnessed a kaanugon and it is full of emotion that it gave me goosebumps and made the listeners wail in grief.

The serving of liquor during the haya is another practice that has survived generations. Tuba or coconut wine continues to be the liquor of choice served in Catigbian.

Keeping the Catigbian Kapunungan Alive

The older members of the Dayong cannot remember who originally formed their Kapunungan. They recall that in their youth, their parents and grandparents were already members of the Dayong.

Today, their married children are members too. These young members will ensure that the rituals of the past will be passed on to the future.

—- ⬤ —-

Sources:

History of the Bisayans by Fr. Francisco Alcina

Thanks to Eda for sharing her experience in the Dayong. Thanks to Rev. Fr. Genaro O. Diwa, SLL, Executive Secretary, Episcopal Commission on Liturgy (CBCP) for sharing his thoughts on the 40th day rite for the deceased.

Leave a Reply