Or is it the translator?

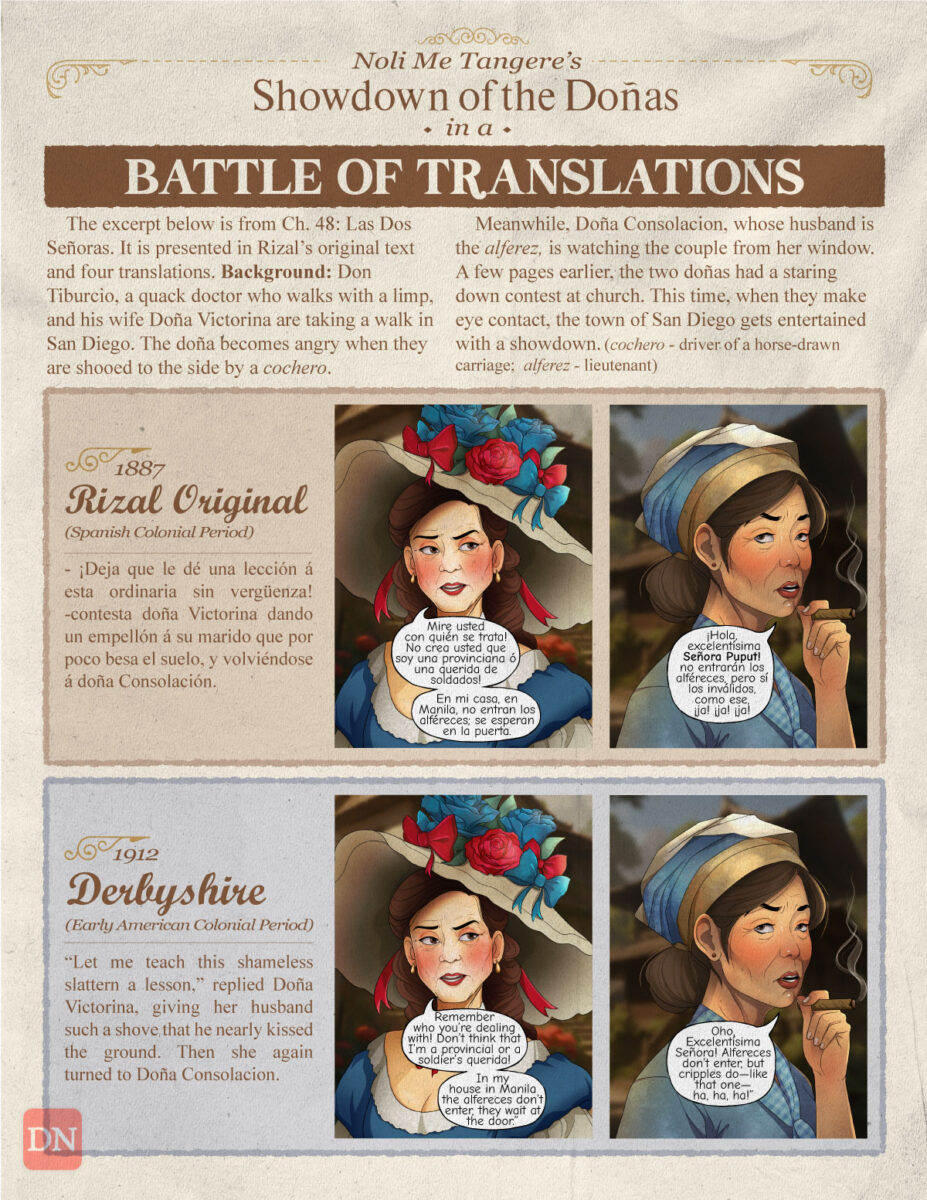

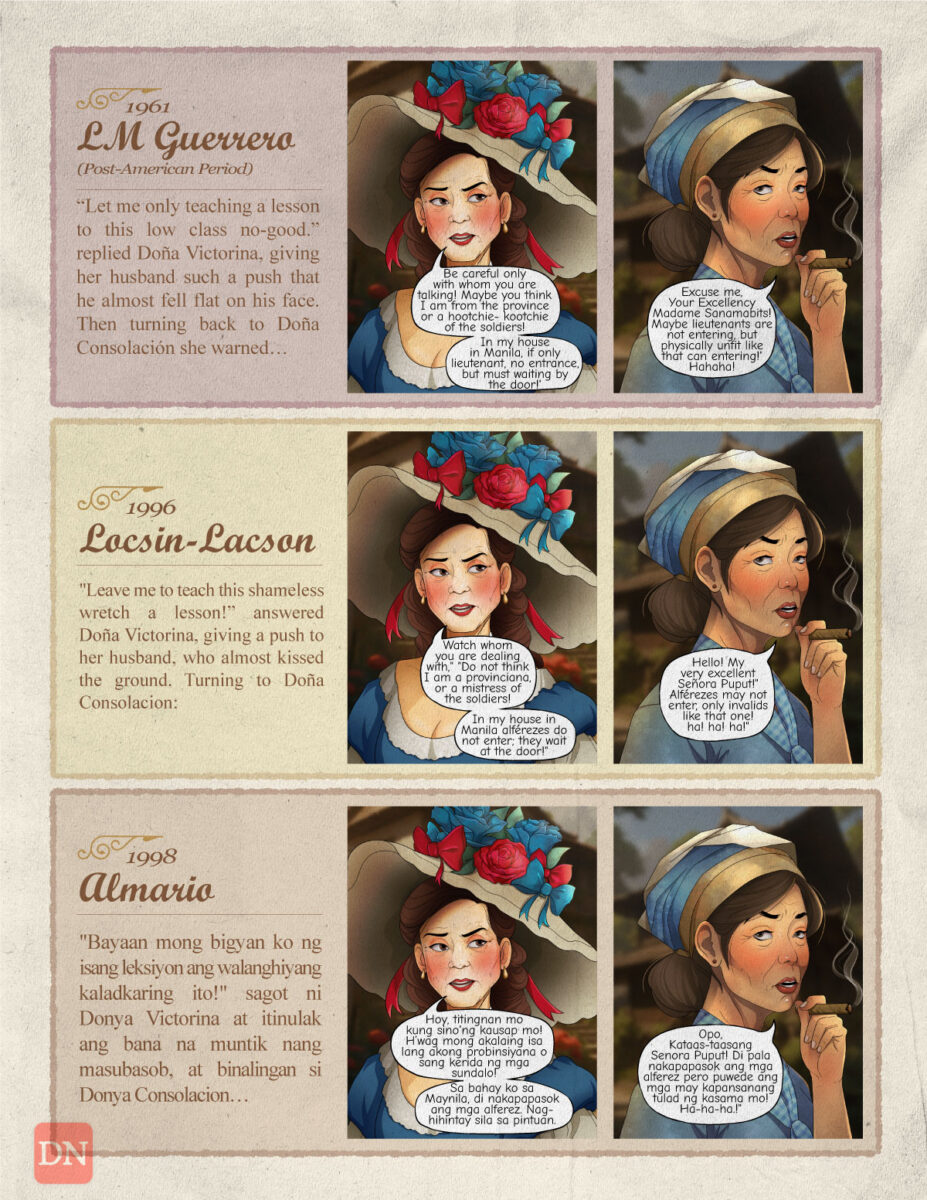

Who is speaking in the Noli Me Tangere? As you will see in the Showdown of the Doñas illustrated here, Rizal and the translator both express themselves in a Noli translation.

Translators bring a piece of themselves to the story. What readers experience is the translator’s interpretation of Rizal’s original Spanish text. Do we lose Rizal in these translations? In many instances, yes. But for us non-Spanish language speakers, we have little recourse. To read Rizal who wrote in Spanish, translations are a necessary evil.

Rouge and Pretense

The two Doñas like to wear make-up and to pretend they are more Spanish than other people. Doña Victorina speaks only Spanish, albeit badly. Doña Consolacion, on the other hand, is described as having forgotten her Tagalog but could not make herself understood in Spanish.

Leon Ma. Guerrero dares to interpret Victorina’s speech

Guerrero is the lone translator who shows that Victorina spoke the Spanish language badly. He interprets this as broken English.

Sanamabits and bits

True to form that Doña Consolacion has forgotten her Tagalog, Rizal lets her use the word puput, which most likely means putang-ina-ka. Guerrero translates puput as sanamabits. Derbyshire edits the word out. The other translators maintain the word puput. Elsewhere in Rizal’s original, the alferez calls his wife p…. – and that obviously means sanamabits or just plain bits.

The Derbyshire translation of the Noli

Rizal wrote his novel in Spanish and added a generous serving of Filipino words. In his translation, the American Charles Derbyshire kept over a hundred Filipino and Spanish words that are peculiar to Filipino culture. These words would have lost their flavor if they were translated to English. Aswang, tabi, hermano mayor, and tulisan are some examples.

While querida appears in Rizal’s original in its two meanings, Derbyshire retains it as the Filipino word for mistress. When querida refers to the object of one’s love, Derbyshire translates it to the English beloved.

Derbyshire opted to include a glossary in his translation. In my first blog, I mentioned that Guerrero, did the opposite of Derbyshire. Guerrero translated “even culturally unique words which lose their flavor in another language … for example, banka is boat, mankukulam is magician, galletas are biscuits, and salakot is straw helmet.”

Spoiler Alert: Medical Mystery Revealed in Translation in El Filibusterismo

After cutting trees in a patch of forest, the family of Cabesang Tales in El Filibusterismo all came down with a fever. His wife and a daughter died from what Tales believed to be the revenge of the spirits in the forest.

Rizal leaves certain things out of his novel like the cause of the fever. Was the omission by design? I believe so. But since the Noli is over a century old, I appreciate Derbyshire’s diagnosis of MALARIA.

Additions: Is it Rizal speaking in the Noli Me Tangere?

Is adding to the text a sin in translating? As I mentioned in my first blog, Guerrero liked to add context to his translation. For example, in the chapter where Rizal introduces the bosses of the town San Diego, the translator clarifies which religious order Rizal is alluding to.

“In a month after Fr. Salvi’s arrival nearly everyone in the town had joined the Venerable Tertiary Order, to the great distress of its rival, the Society of the Holy Rosary sponsored by the Dominicans.” The devil… “shied away from a napkin painted with the crossed forearms of the Franciscan Order and fled from its knotted cincture.“

The words in bold were added to Rizal’s text by Guerrero. These additions may not have been necessary in Rizal’s version in 1887, but today, these descriptions help the reader understand who Rizal is alluding to.

What surprised me was the Tagalog version of Poblete. He edited out sentences from the original Spanish. Gone is the Maria Clara who wanted to hear Elias speak. Gone too is the Maria Clara and the rest of the party who admired Elias’ physique. This translation sucked out the red blood of Maria Clara. No wonder Rizal was boring when we studied him in high school. Parts of his work had been deleted.

from my first blog, Elias kisses Maria Clara’s Portrait

Omissions: Losing Rizal in the Noli Me Tangere

Omission is the graver sin in translations. Catholic schools opposed the teaching of the Noli and Fili. When the Rizal Law was signed in 1956, a watered-down version of the novels became acceptable in Catholic schools.

According to Marlon James Sales, the translations of Salazar (1999) and Miranda and Tulaylay (2006) omitted the discussion about purgatory by the character Tacio.

Strange creatures in Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere

When there is no direct translation of a word, a translation can become a strange creature as they can evoke imagery not intended by the author. Take for example, the sentence which describes the strength of Elias. He had …powerful muscles that helped his bare sinewy arms handle, as though it were a feather, the enormous oar….

In the original text, Rizal used the word pluma which means either feather or a pen made of feather. The two Filipino English translators Locsin-Lacson and Guerrero wrote feather, which is what Rizal intended. Derbyshire translated it to pen, which doesn’t really make sense in the sentence. Pascual Poblete called it isang balahibong ibon while Virgilio Almario called it isang pakpak-panulat. The Tagalog translation made me think of a bird and a wing. Perhaps the Tagalog translators should just use the Spanish pluma or allude to something that is light like the tukog.

Which translation do you prefer?

Do leave a comment to let me know which translation you prefer.

—- ⬤ —-

More on Noli Me Tangere

—- ⬤ —-

On Another Note

Leave a Reply