A Must Do in Boracay : Ride a Paraw

Every late afternoon, when the weather and the coast guard permit, sailboats called paraws rush out to sea from the island of Boracay in the Philippines. Tourists who ride these paraws enjoy a sunset cruise and, though they may not realize it, they also catch a glimpse at how ancient Visayan seafarers sailed from island to island.

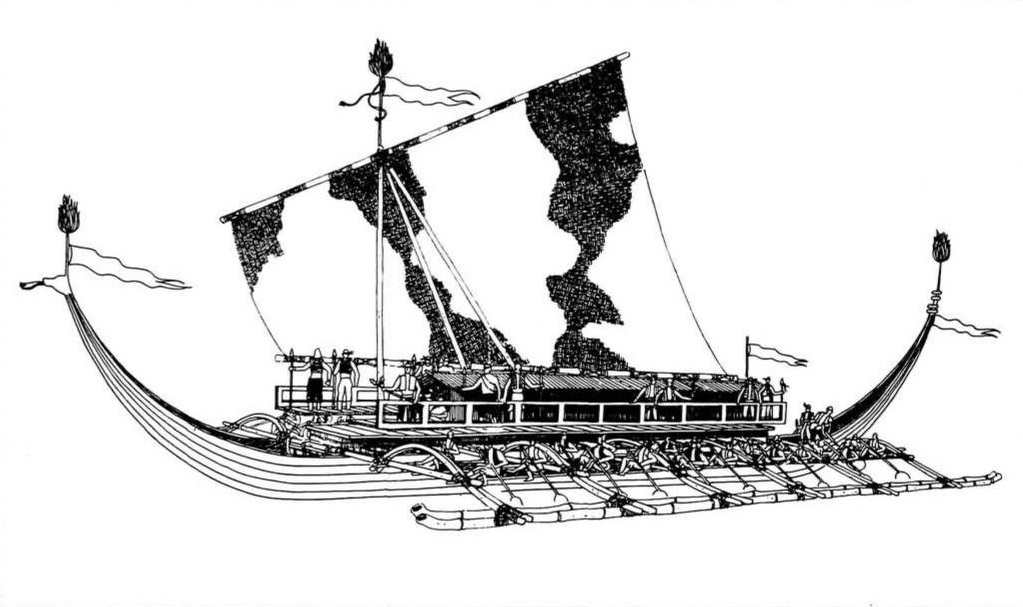

Visayans had a great variety of sailboats before steam ships and motorized boats became popular in the 19th and 20th century. The first Spanish visitors in the country described them: they ranged from the single-sail canoe with outriggers called baruto which was made from a single hollowed tree trunk to the bigger balangay that carried families and cargo, to the large karakoa cruisers that ferried warriors.

Although I have seen a baruto in the different places I have visited in the Visayas, I only got to ride a sailboat last month during my first visit to Boracay.

As the the paraw sailed to deeper waters, I smiled, pleased with the sensation of speed. My companions and I exchanged looks of exhilaration when we realized that the paraw moved faster than any pump boat we’ve ridden. The sun was setting and each time gusts of winds would strike, the paraw would heave up from the water. We laughed off the tension whenever the boat smashed into the water and got our clothes wet. We were sailing at 12 to 13 knots, a crewman said. I now appreciate why many sailboats have the word flying in their names.

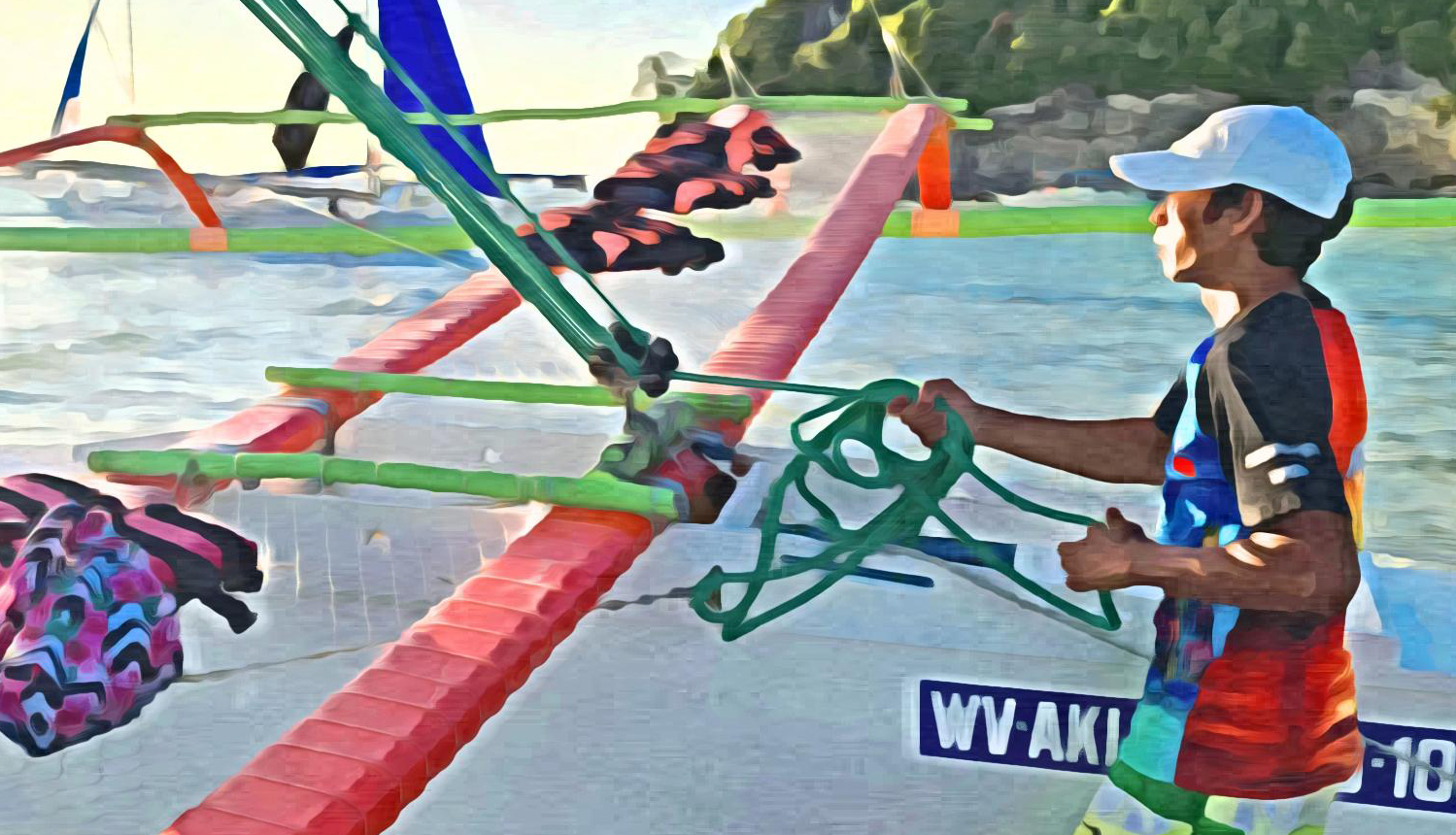

Sails of the Boracay Paraw

The paraw has two sails, an outrigger or katig on each side, and a slim single hull. I say slim because among the Philippine boat hulls that I’ve seen, the paraw has the narrowest body for its length. Both sails are triangular, with the smaller one called pook in the front. The main sail is called layag and in Visayan, the verb nag-layag means a sailor has caught a strong and steady wind. It can also mean being a front runner with a comfortable lead in any kind of race.

In ancient times, when the hull filled with water, the sailors jumped into the sea and used their oar or bugsay to bail the water out. The blade of the bugsay was shaped like a dinner plate or a gourd cut in half and left hollow to be an effective water bailer. — Sources: Fr. Francisco Alcina in History of the Bisayan People and William Henry Scott

The crew distributed us as equally as they could on each side of the paraw. We sat on what they call a batik — a plastic wire mesh around two feet wide held together by two parallel wooden planks balanced on the boat. The planks extend up to the bamboo katig. This means we sat outside the hull, less than a meter above the water.

The planks are reminiscent of how the ancient Philippine boat builders created sailboats. The panday, which was how every craftsman was called, added bamboo poles or wooden planks on a base. Then he fastened these with rattan or wooden nails to allow more cargo or passengers on the boat.

The Monsoon Winds

As we headed south, I asked our Captain Noel where the wind was coming from. He gestured to the shore with his chin and then pointed his finger northeast. The wind was hitting the side of the sail he said. I asked if the wind was still Amihan and he answered “yes, it will be here until May.” Habagat — the southwest monsoon — would come in July and last up to October. After that, the wind shifts to Amihan again, he explained.

What happens when there is no wind to power the sails? “We paddle,” our captain responded. Unlike other sailboats, the Boracay paraw doesn’t have a motor. Captain Noel and his crew would find affinity with the ancient Filipino sailors who paddled furiously when the winds died down. Each child living by the shore knew how to paddle well. An oar was made for the child equal to his strength, according to chronicler Fr. Francisco Alcina in the History of the Bisayan People (1668).

Habagat winds are usually stronger than Amihan winds, our captain shared. Sometimes, during Habagat, the sailors move the sunset cruise to the eastern side of Boracay where the waters are calmer.

Were the Monsoon Winds Gods?

In 2012, the Philippine Postal Corporation issued folklore stamps featuring Amihan and Habagat as gods. According to the PHLPost website, the characterization of Amihan as a god is based on a Tagalog myth. The webpage on Habagat calls him a god of wind and rain.

In pre-Hispanic times, each indigenous group of people in the Philippines had their own myths and legends. Alcina’s History of the Bisayan People, which focused on Leyte and Samar, doesn’t identify Amihan and Habagat as deities. They are found in the chapter about winds and they play no part in the chapter concerning God and divinity. As to the origin of winds, Alcina says that “the natives believed that the winds sprang up in subterranean caves.”

Though the monsoon winds were not gods, the winds did command when it was the best time to sail from one part of the archipelago to another.

To Sail Again

When the crew delivered us back to the shallows of Boracay, they shared that they were joining a paraw race. We wished them good luck and thanked them for our sailing adventure.

As I waded to the shore, I thought it would be nice to go sailing again soon. Next time, I want to try my hand at the sails.

—- ⬤ —-

Leave a Reply