Three Personal Accounts

While reading Rampage by James M. Scott, I thought of the World War 2 personal stories that my aunt shared with me. She is gone now. As I tried to write down her stories, I found that there are gaps in her narrative which I couldn’t fill. This made me realize the importance of recording and writing what our elders share with us. Recently, I interviewed those around me who have memories of World War 2.

Here are the narratives of three WW2 witnesses. I share their stories so we may recognize their sacrifices and remember the loved ones they lost.

Carmen’s Memories of World War 2

Bandits as Guerillas

Before the enemy forces of Japan arrived in Leyte, a gang of bandits entered the home of nine-year-old Carmen and seized her father, grandfather, and aunt. The bandits introduced themselves as guerrillas under a Filipino leader named Blas Miranda. The captured family members were led out of the house and into the mountains.

Orphaned of their mother who died while giving birth, Carmen and her two younger siblings lived with their father and paternal grandparents. Their home in Merida, Leyte stood by the sea and near their farm where abaca, corn, sugar cane, and rice were cultivated.

During their trek to the mountains, Carmen’s aunt Remedios, who had a limp, slowed down the escape of the bandits. Because she could not keep pace with the group, she was allowed to turn back to the house. Later, Carmen’s father and grandfather would be rumored to have been beheaded. The bandits threw their bodies over a ravine, people said. Carmen never saw her father and grandfather again; their remains were never found.

Flight

As soon as Carmen’s aunt Remedios arrived home that day, Remedios placed Carmen and her siblings under the care of their maternal grandmother Catalina who lived nearby.

Remedios and her mother went over their plans of escape while an employee urged them to leave as quickly as they could. In those days, the roads connecting Merida to Ormoc were not yet paved. Boats were the main mode of transportation and all agricultural products were shipped by sea to market or to the sugar mill. Carmen’s grandmother and aunt left on a banka paddled by their loyal employee. They headed for the town of Ormoc.

Death of Sons

Late that afternoon, Pablo, a brother of Carmen’s father, arrived in Puerto Bello. He had ridden on his lancha, a motorized boat, with the intention of rescuing his mother. He did not know his mother had already fled. Just as he alighted from his boat, bandits shot him.

As Pablo lay dying on the beach, he must have heard the reason for the bandits anger toward his family. They said he was a Japanese sympathizer because he had been to Japan.

Before the war, Pablo visited Japan to learn about shipbuilding. He was interested in engineering and he took care of the family’s farming equipment. Together with this wife, he also founded a technical school. Pablo’s dream for the family to have its own shipping line would end with his death.

In the course of the war, another paternal uncle of Carmen went missing in Manila. Thus, by war’s end, Carmen’s paternal grandmother lost all her male children.

Japanese Occupation

During the Japanese occupation of Leyte, Carmen’s maternal grandmother Catalina deemed it was safer for them to keep on the move in the mountains. Especially toward the end of the war, they had to move often and Carmen’s three maternal uncles led the setting up of each new camp. As they evacuated from a camp, Carmen and her family trekked across rivers to hide their tracks under the water.

They ate rice, corn, and cardaba bananas. Chicken was available. Pig was scarce but when it was available, they salted it raw and placed the cuts of meat in a coon or clay pot. Monkeys from the forest competed with them for the harvest of corn.

Liberation

When the Americans came back to the country, there was a lot of dogfighting. To Carmen, the sound of gunfire seemed to start from the mountains and end at the Ormoc Bay where the losing plane would crash.

With the coming of the Americans, Carmen’s paternal grandmother came home and turned their house into a temporary infirmary to treat Filipinos. Many were malnourished and had swollen feet because they had subsisted only on a diet of ubod (young coconut tree’s core).

The American soldiers set up camp near the family farm and their presence was seen as a business opportunity. A relative taught Carmen and her cousin how to distill alcohol. Using a steel barrel as a stove, they distilled tuba or coconut wine and baked bread to sell to the American soldiers.

Justice Denied

After the war, Carmen’s family wanted to file charges against Miranda, but they learned that the Philippine President Sergio Osmeña issued an amnesty for guerrillas.

A couple of years ago, a local TV station interviewed Carmen and her friend Antonia about their experience during the war. This occasion made them reminisce about the persecution both their families experienced under Miranda.

Carmen is 92 and enjoys spending time with her friends and family.

Romy’s Memories of World War 2

The Parade

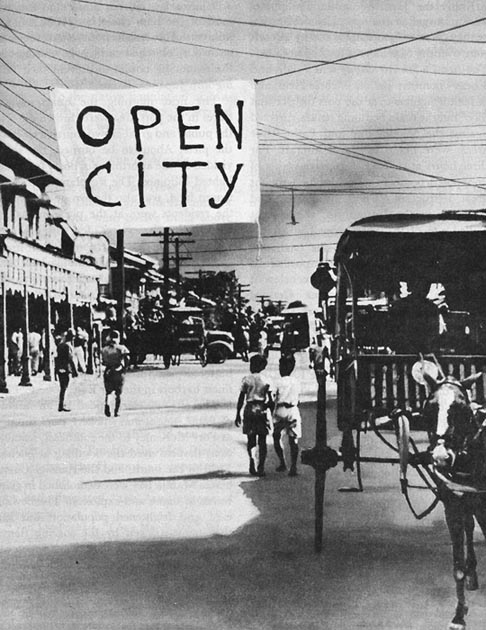

The Japanese army awed nine-year-old Romy as it marched in cadence through Paco in 1941. The army was on its victory parade after Manila was declared an open city by United States General Douglas MacArthur. As an open city, the Japanese were free to occupy Manila. It was a move meant to save the city from destruction and minimize casualties.

The Japanese soldiers on horseback impressed Romy the most. It crossed his mind that the discipline exuded by the army was why the Japanese were able to push out the Americans from the Philippines.

Back to school and play

In the beginning, the Japanese occupation did not change the life of Romy. He did not really feel the presence of the Japanese even if there was a sentinel posted in one of the streets leading to his house. Romy lived along Calle Paz with his mother, his 24-year-old brother Aldo, and 23-year-old sister Bianca.

He continued to attend classes at the Paco Catholic High School, a school run by Agustinian sisters and Belgian fathers. He also continued to play in the streets with his friends.

Softball, marbles, patintero, and jai alai were among their favorites. They drew water from the street canal to create the lines for patintero. For their jai alai games, they used the mud guard of the karetela as rackets and bounced the ball off the walls of their neighbors.

As time went by, Romy’s mother and sister sold their jewelry and even their clothes in order to have money to buy food and other necessities. This made Romy think of ways to make money.

Kokang

He offered to sell his neighbors’ belongings for them. A doctor commissioned him to sell a hat — “he had many hats” Romy recalls. He was able to sell it on Calle Herrán (now Pedro Gil St.) and Romy eventually sold most of the doctor’s hats.

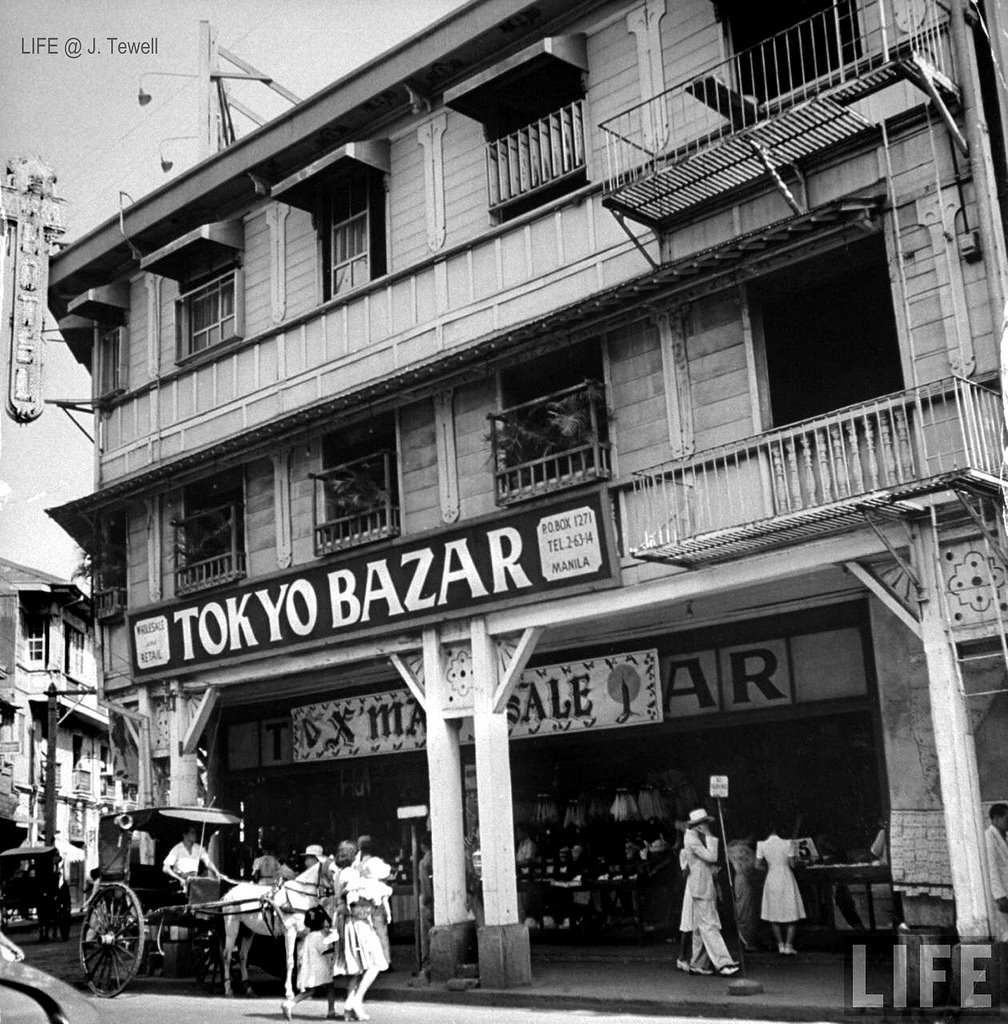

Herrán, which stretches from Santa Ana to Dewey Boulevard (now Quirino Ave), was “where most of the trading was done,” Romy muses.

Through his friends, he met a supplier of rum which he peddled to the Japanese. In return, the Japanese gave him cigarettes — usually the Akebono brand. (Cigarettes were scarce during the Japanese occupation.) Romy recalls that trading with the Japanese was called kokang. For a young person, he was good at it, he says with amusement.

One evening, the Japanese sentinel on Oregon Street slapped Romy for being out on the street late at night. But what pained Romy wasn’t the slap but the confiscation of his bag of cigarettes which he had planned to sell. From then on, he did what many Filipinos did… he evaded the street with a sentinel and took a longer route home.

Madame Stella

A few of his friends brought Japanese soldiers to Madam Stella who headed a prostitution den along Ermita. Madam Stella invited then 12-year-old Romy to pimp too. His friends informed him of a bonus: after bringing in four customers to the brothel, they got time with a prostitute for free.

The money was easy. The invitation was tempting. But his brother warned him that if he ever heard he was pimping, that Romy should look for another home.

Food Scarcity

From his kokang, Romy was able to help his family put food on the table. Beef was scarce but pork, chicken, fish, and vegetables were available. He enjoyed fried camote with brown sugar for breakfast. Coffee was also available during the earlier part of the occupation. But later, he recalls that roasted corn grits were mixed in the family’s coffee. His mother also combined milled corn in their rice.

As food became scarcer toward the end of the war, Romy marveled at how his mother was able to feed everyone with less. She mixed in more sauce and potatoes into her dishes. “I could not really say that I went hungry but I always had the feeling that we were not getting enough. As the years went by, it became more and more difficult.”

Fort Santiago

Romy’s older brother Aldo was picked up by the Japanese on suspicion of being a guerrilla. Aldo was incarcerated in Fort Santiago and released one month later. Romy did not recognize his 6-foot-2 brother when he was released. His face was disfigured from the beatings he received in prison.

Toward the end of the war, Romy relocated to Ermita with his sister who ran a bar there while the rest of the family remained in Paco. Moving to Ermita was a decision he would regret because it would put his life in danger.

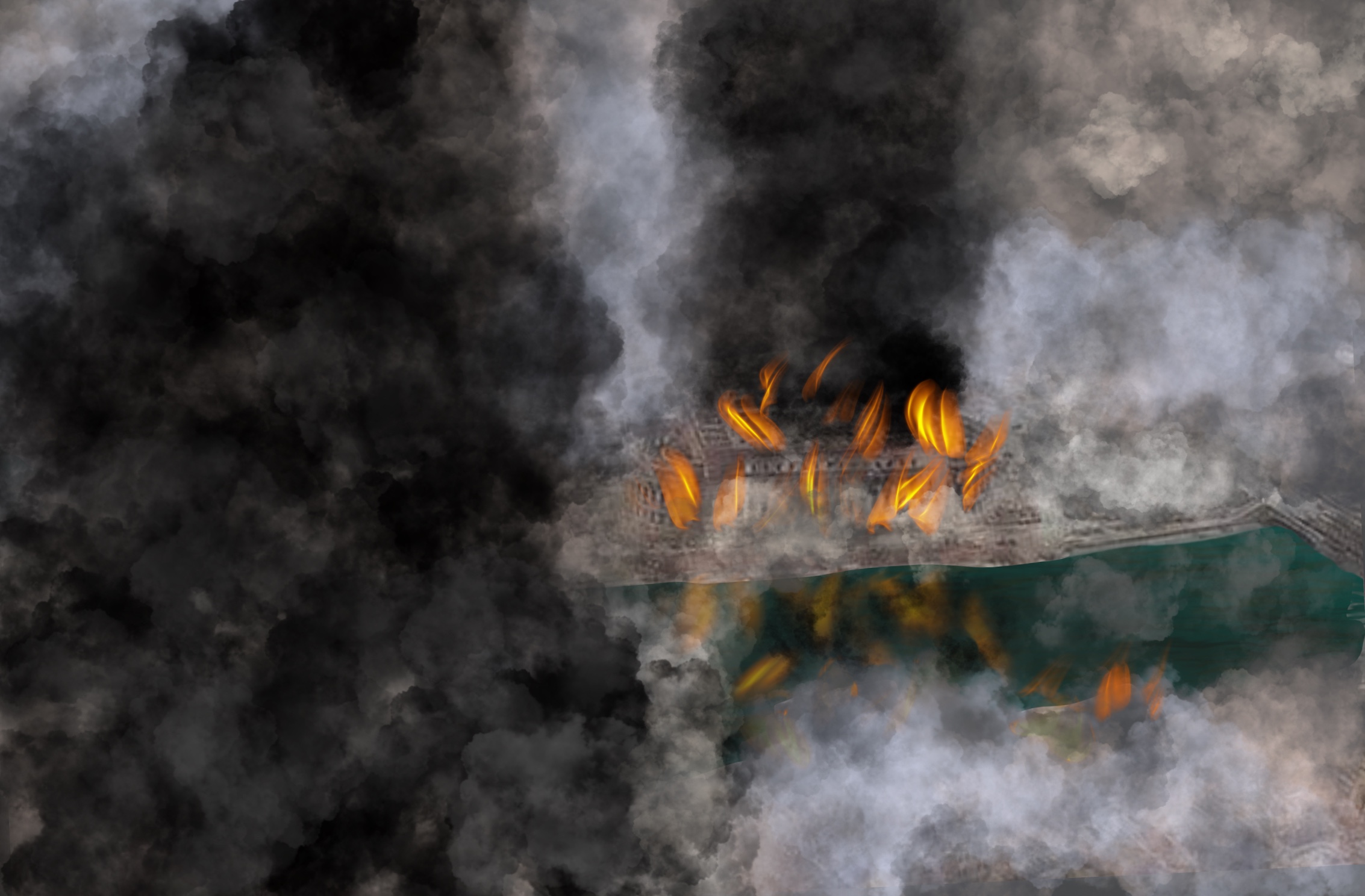

Manila Burns

On February 9, 1945, there was gunfire in Ermita. The Japanese and the Kalibapis commanded the residents out of their houses. Kalibapis were described by Romy as Filipino supporters of the Japanese.

The Filipinos were instructed to form two lines, one for men and the other, for women. His sister quickly threw a shawl on top of his head and told him that he should stick with her and the women.

The enemy soldiers brought the women to the Bayview hotel and the Filipino men to the Manila Hotel. At the Bayview Hotel, soldiers picked out young women from the group and brought them to another room.

Romy said one of the older women presented herself to be taken by the soldiers instead of the young women. When I told Romy that this part of his narrative is described in the book Rampage, he paused. She was a memory to him, and at times, he thought he imagined her, he said. He was dumbfounded that his recollection was real and that the beautiful and courageous woman really existed.

After two days at the Bayview, they had to evacuate. “The building was burning and we were on the fifth floor. The wall was very hot as we went down the stairway,” recalls Romy.

The Water Run

They moved out of the hotel and transferred to the Luneta Hotel and later to the Luneta park. There they found sawali mats to shelter themselves from the sun. Water was scarce and many drank the water that pooled in a huge crater gouged by a bomb. The women used their clothing to filter the water.

Romy’s sister decided there was a better source of water nearby and gathered some bottles. Every evening from February 13 to 22, Romy ran to the nearby Army Navy Club. He evaded a Japanese pillbox in the corner and crawled along certain parts of the way and then filled the bottles with water from the Club’s swimming pool. He did this around two to three times a night in order to share the water with other women. Romy was able to accomplish his water runs without catching the attention of the sentry.

Liberation

Romy’s birthday falls in February and it was a particularly happy birthday for him in 1945 because on February 22, the American soldiers appeared at the Luneta. According to Romy, the women screeched with joy when they saw the Americans.

Today, Romy is 92 years old. He had a successful career as a business executive for various corporations. He is fully retired now and enjoys spending his mornings on a paseo with his great grandson

Isidro’s Memories of World War 2

Eleven-year-old Isidro learned that war was coming when he went to school and found it closed. Before the news of war, he attended classes daily at the Giloctog Elementary School in Barili, Cebu. Barili is situated by the shore and on weekends, Isidro went fishing to help augment the family income.

Fishing

With school closed, Isidro went fishing daily. One day, as they were about to dock on the shore of Barili, he saw a group of Japanese men in uniform. That moment made him realize that the country was indeed at war. He observed the soldiers and, although they did not harm him, he found them sinister in their caps which had leaves on them.

Barili was peaceful even with the presence of the enemy. As the Japanese occupation progressed, his grandmother Simprosa decided to go to Negros to be with her youngest son. She left her other children and husband in Barili, and brought Isidro with her to Negros.

Negros Island

In Negros, in the mountain barangay of Tacpao, Guilhulngan, Isidro and his uncle Baslio planted and harvested rice, bananas, corn, camoteng kahoy, and camote. Ginamos or fermented fish and buwad or dried fish were part of their diet.

The Bamboo Gong

The farmers in the barangay formed an association to guard against the Japanese. They constructed a payag (hut) near their look-out, and this was where they rested during their shift. In the middle of the payag, the men placed a bamboo gong which they called tultog. It was agreed that if Japanese troops came, the gong would be sounded to alert the residents.

Isidro’s uncle Basilio was part of the group and he reported for guard duty one day a week. Whenever Basilio could not perform his duty, Isidro took his place. Around 10 to 12 Filipinos would stand on guard each time, with everyone signing an attendance sheet. At 13 years old, Isidro was the youngest guard.

Everyone brought in their own food which they shared with each other. Isidro fondly remembers enjoying sikwate (chocolate drink) brought by another guard.

One day, the barangay heard the sound of the tultug. Isidro’s neighbors came running out of their homes to ask if there were Japanese soldiers coming their way. Indeed, there were. In fact, it was the Japanese who sounded the alarm. Isidro’s family and neighbors ran to the forest to hide.

The Japanese killed many of Isidro’s neighbors and relatives. One member of the association shot dead two Japanese sentinels and injured three others. The Japanese hacked him in retaliation.

After the battle

When the sound of gunfire finally abated, Isidro and his family came out of their hiding place and went back to their homes. The Japanese soldiers, however, had burned down all the houses. After this event, Isidro heard that American soldiers had arrived and Japan had lost.

Isidro and his family immediately rebuilt their house using palwa (branch of coconut tree) and lukay (coconut leaves) for roof and bed. Eventually, they were able to rebuild their house using cogon grass for roofing.

Going Home

Isidro and his grandmother eventually went back to Barili. Back home, Isidro learned that the Japanese became brutal and dumped the bodies of Filipinos over a deep ravine.

Isidro went back to fishing and one day, as his boat was about to dock, he saw some American soldiers with Filipina women. They gave him Caramelito candies and he remembers that he liked them very much. The sight of an amphibious tank amazed him too.

Back to School

When he went back to school, this time in Barili Central Elementary School, he noticed there were two flags flying. They were the Filipino and American flags. Isang bayan, dalawang bandera he remembers calling it.

After six months in school, Isidro passed an exam and he qualified to move up to Grade Four. Later, Isidro decided to become a full-time fisherman.

Isidro fished up to when he was 87 years old. Today, he is 94. His children and extended family are his next door neighbors in the same mountain barangay in Barili where he lived as a child. He stays mostly at home tending to their goats which they won in a senior citizen’s raffle. His 80-year-old wife still gathers wood which Isidro chops into smaller pieces for firewood.

—- ⬤ —-

End Notes

Korean Conscripts. When asked about Korean soldiers during the war, the three witnesses echoed the recollection of many survivors: that the Koreans were more atrocious than the Japanese. Isidro does not recall having first hand experience with the Koreans. Romy and Carmen could not remember how they could tell the Koreans apart from the Japanese soldiers. They remember that they wore the same uniform. Could it have been the soldiers’ demeanor? Or could it have been that cruel acts were attributed to the Koreans by the Japanese? Could Korean cruelty have been a smear campaign against them to improve Filipino perception of the Japanese?

According to Ateneo de Manila University Political Science Professor Lydia N. Yu Jose, there were very few Koreans assigned in the Philippines, with many of them assigned to civilian tasks. “Out of over 600 Korean POWs, 13 were tried by the US Military Commission in Manila. Of the 13, only two were convicted. One, a Korean of Japanese citizenship was sentenced to death by hanging.” Read more here about why the Koreans don’t deserve the general perception of being pervasively cruel.

By the way, the book Rampage does not mention Korean conscripts.

—- ⬤ —-

Would you like to ask your elders about the war? Here are some Guide Questions.

How old were you during the war? Where were you staying? How did you spend your days before the war started? During the war, what made you happy? Sad? Scared?

What did you eat? Where and what did you get to play? Did you go to school? Did you encounter a Japanese? What was your worst experience? Did you have any regrets? What were your best days like? Who was your best friend? Did you dream? What did you miss the most?

—- ⬤ —-

Watch #KronikaMilitar ep. 09 – Battle of Manila 1945: Causes and Consequences of Tragedy. This podcast includes a discussion on misconceptions about the war. The historians cite the importance of a collective memory about the war.

Leave a Reply